- Home

- Blaine L. Pardoe

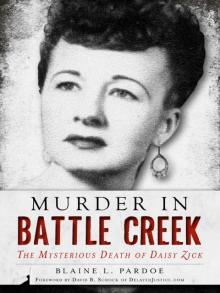

Murder in Battle Creek

Murder in Battle Creek Read online

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright © 2013 by Blaine L. Pardoe

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.589.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pardoe, Blaine Lee, 1962-

Murder in Battle Creek : the mysterious death of Daisy Zick / Blaine L. Pardoe.

pages cm

Summary: “On a bitterly cold morning in January 1963, Daisy Zick was brutally murdered in her Battle Creek home. No fewer than three witnesses caught a glimpse of the killer, yet today, it remains one of Michigan’s most sensational unsolved crimes. The act of pure savagery rocked not only the community but also the Kellogg Company, where she worked. Here, Blaine Pardoe artfully takes the reader into this true crime thriller. Utilizing long-sealed police files and interviews with the surviving investigators, the true story of the investigation can finally be told. Who were the key suspects? What evidence does the police still have on this five-decades-old cold case? Just how close did this murder come to being solved? Is the killer still alive? These questions and more are masterfully brought to the forefront for true crime fans and armchair detectives”--Provided by publisher.

Summary: “An examination of the unsolved 1963 murder of Battle Creek’s Daisy Zick”--Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-62619-134-1 (pbk.)

1. Zick, Daisey, -1963. 2. Murder--Michigan--Battle Creek. 3. Murder--Michigan. I. Title.

HV6534.B38P37 2013 364.152’3092--dc23 2013021369

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews

To my wife, Cyndi, who puts up with my writing and gives me encouragement even when she doesn’t realize it. To my kids, Alexander and Victoria—and my grandson Trenton—you never know where the information will take you. To my mom, Rose Pardoe, who has been anxiously waiting for me to finish this book.

Finally to Central Michigan University, my alma mater.

CONTENTS

Foreword, by David B. Schock, PhD

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1: Daisy’s Last Day Alive

2: To the Bitter End

3: The Mysterious Man on Michigan Avenue

4: The Affairs of Daisy Zick

5: New Hopes

6: The Cold Sets In

7: A New Generation of Investigators

8: The Prisoner, the Postman and the Ever-Chilling Trail

9: Twilight

10: The Myths and Theories

Epilogue

Timeline: January 14, 1963

About the Author

FOREWORD

Somebody knows something. Somebody always knows something.”

The speaker was Jim Fairbanks, a retired detective who had served his career with the Holland Police Department (HPD). Jim had worked for decades with that department and had—long before our conversation—headed the city’s efforts to solve the 1979 abduction and strangulation of Janet Chandler. By the time I spoke with him in 2003, he was long off the job and had a lot of time to think about the case, which just would not be solved. This was the case that kept the members—current and former—of the HPD up at nights, wondering. Above all else, Jim was certain that somebody knew something about the crime; it hadn’t happen in a vacuum. And it was his certainty that helped to drive us to share the story of Janet’s murder in the documentary Who Killed Janet Chandler? (For more about this, please see my website, www.delayedjustice.com.)

Over the intervening years, I have quoted Jim again and again. Almost always, somebody does know something. In most murder cases, somebody has either witnessed something relevant or listened to someone talk about the event, perhaps voiced in a threat or a confession. We believe that most often somebody besides the killer knows what happened.

And sometimes as a result continued prodding, the truth will come out. Geoffrey Chaucer, in the “Nun’s Priest’s Tale” of The Canterbury Tales, put it this way: “Murder will out that we see day by day.”

We do. And it’s marvelous when that happens. In this day and age, we see great strides in solving murders from decades before, thanks to the employment of new technologies, DNA chief among them. Sometimes it’s just dogged determination, even when there is no forensic evidence. Many departments have devoted the time of senior detectives to what they are calling cold case units. Other agencies have convened interdepartmental task forces. The results have been both stunning and welcome.

But not every case responds to such an approach. So far, for instance, the 1963 murder of Daisy Zick has been stubbornly resistant. And now it falls to the historian to have a shot at retelling one of the most baffling of all Michigan murders.

Blaine Lee Pardoe is a historian who publishes prolifically. He’s also a very friendly and approachable person, someone you actually could—and would want to—talk with. He and I met in the fall of 2011, when each of us was receiving an award from the Historical Society of Michigan: he for his book Lost Eagles: One Man’s Mission to Find Mission Airmen in Two World Wars and I for my film about Detroit’s Poet Laureate, Star by Star: Naomi Long Madgett; Poet & Publisher. Blaine’s book offered a careful telling of the story of Frederick Zinn, a man who devoted his life to bringing home the remains of lost American airmen. Along the way, Zinn developed techniques that would serve all searchers. The book had been published by the University of Michigan Press and was a lovely example of fine work between an author and a publisher.

If that had been Blaine’s sole contribution, it would have been enough. But as we chatted that evening, I learned that he had done so much more, including a then-forthcoming book about a murder, Secret Witness: The Untold Story of the 1967 Bombing in Marshall, Michigan, another University of Michigan collaboration. And there was another murder book in the works after that: this one.

Well, three books doth an author make.

But Blaine had written so very many more. As I was to find out later, there are more than sixty titles to his name, and they deal with military history, true crime, computers, games and gaming and business management. And then there are all the online publications and nearly countless articles; he’s a veritable polymath. He says he has a life other than writing and gives credit to his wife, Cyndi; children, Victoria and Alexander; and grandson, Trenton. He also has a day job.

So when I was asked to write this introduction, I jumped at the chance. The reason first and foremost was that I’d have a chance to read the book before you did; I was eager. Beyond that, it’s nice to have something to do with highly productive people; they are different from the rest of us. And finally, I might have an opportunity to assert to readers that Blaine’s work with worthy of support and encouragement.

And what a subject he’s chosen this time.

Unsolved homicides can be difficult to chronicle, especially those that I call “delayed justice” cases, the old and cold. (Believe me, there is nothing “cold” about a murder to a family member of a victim; it is always present and current.) This is a case that is now fifty years beyond the event. It’s possible, perhaps even likely, that the killer has gone to his (or her, as Blaine points out) fi

nal accounting. And the records may be there but likely are in some ways incomplete or deficient. And many who took part in the investigations and who could have filled in the missing pieces have gone on as well.

But just because the case is from a bygone era doesn’t mean that it might not be solved. Time is not always the enemy of truth. People age and change. Sometimes they grow courageous or refuse to be further intimidated; sometimes they find religion or faith. Sometimes those who once terrified them die, and the carriers of knowledge are freed from the oppression of fear. They may marry, divorce, have children or even grandchildren. Or, on their deathbeds, the murderers or those who know about the murders may want to clear a guilty conscience. The future is always unknowable, and any number of things can and do happen that lead to the result that “murder will out.”

Blaine has employed his skills as a writer and his training as a historian and combined them with the healthy imagination he displays in his fiction to give us an honest and unvarnished reporting of the fate of Daisy Zick.

Blaine makes no pretense of his qualifications: “I’m an author and historian; not a detective.”

Well, yes and no.

Any good historian is something of a detective. There is the drive to find the real answers to unknowns, the desire to fill in the blanks. Any solid historian shares that vital curiosity with a good detective. I suspect what he means is something other—that he doesn’t think like a sworn officer of the law; he thinks differently.

It’s good to bring that kind of outside thinking to a murder investigation. Police have told me as much. And they’ve also told me that sometimes our associates—researchers and others with special skills—add to the strengths of the team looking for answers. One officer once told me, “Doc, you have some interesting friends.” He was referring to a professor of forensic psychiatry and a graphoanalyst whom I’d asked to consult on a case. Blaine also brings his own team.

And then there are the readers, who are also self-selecting members of a broader team. There is always the possibility that a reader will discover a connection to a crime that had been previously unknown.

Even I fall into this category for this book. Only three years after the murder, I enrolled at Albion College, a small liberal arts college not too far from Battle Creek. One of my classmates was Ken Zick. Ken had family in the area. My supposition is that Daisy may have married into a branch of his family. (Ken has more recently said he was unaware of either a Daisy Zick or the Daisy Zick murder; he’s now investigating, too.)

But you don’t have to have a connection to this murder to find it interesting. It remains, after all, a great unknown, something of a rarity of the time. In the first place, it was a suburban murder, and those, according to statistics from the U.S. Department of Justice, accounted for a little more than 7 percent (610) of all murders in the United States (8,640) in 1963. (By comparison there were 14,748 murders in 2010.)

Daisy Zick’s murder was one of only 283 in Michigan in 1963. (That compares with 567 in 2010; the highest number was 1,186 in 1974.) Moreover, it was one of very few unsolved homicides. In 1963, more than 91 percent of all homicides were cleared by arrests or other extraordinary means. And that’s a far better percentage than the 64 percent clearance rate in the United States in 2008. The rate is far lower than that in Michigan; the Michigan State Police in the Michigan Incident Crime Reporting publication put the 2011 clearance rate at 24 percent. I have talked with a statistician at the Michigan State Police who said they are trying to find the reason for the drop. A few years earlier, we had been the lowest in the nation with a 52 percent clearance rate. What a 24 percent rate means is anybody’s best guess. It would seem that you’d have better than a three-out-of-four chance of getting away with murder here. I hope those figures are open to correction, and an upward correction at that. Such a low rate is unsettling, if not deeply distressing for me at least. But then, I take a very dim view of murder; it’s a bad idea, a very bad idea. It violates every precept that’s been handed down to us as a standard for right living. It is an offense against God and man. This intentional depravation of the one thing that ought to be ours—our lives—strikes at the root of a just society.

And yet it happens. And sometimes the killers get away with it.

And sometimes people write books about it or make films or tell stories. We recognize that there is value in retelling the story—it should not be lost to our shared history. And it should stand out because it represents a break from our usual way of going about life, trusting that we can walk out our front doors in safety or relying on fragile glass to keep the outside world outside. In the event of a murder, there is something that upsets the right order. And that jars some of us, people such as Blaine and me and a host of others.

But there are ways of going about it that might be helpful and those that might not be. As Blaine puts it, “Armchair quarterbacking of murders is easy and dangerously seductive to undertake.”

Blaine has not been seduced by the easy answer or the innocent wonderment of it all. He digs deep, speaking with as many people who were around and know the victims and putative suspects.

And he does one other thing I deeply appreciate: he takes the time to look into the backgrounds of the investigators. You will know the circumstances of their lives, their families, the way they speak and their fates. Blaine realizes that each of them left indelible impressions on this case and that those impressions remain. And he notes that, in their way, they also suffered because the crime remains unsolved.

Daisy Zick’s life and that of her husband, Floyd, is laid bare. We know of her serial affairs and that possibility that she may have had several going on at one time. We know of Floyd’s infidelities as well and his predilection to drink. But we also know something of their care for each other; somehow, their marriage worked. And we know that Daisy was a meticulous person in all she did. Had she lived, it’s possible she might have been a very prim little old lady with a tidy house that had everything in its place.

Blaine is not cruel in his revelations of her personal life, a life that must be examined in the context of her murder. He does not make sport of anyone’s failings in this book. The book manages to be interesting without any hint of the salacious. And there is even humor, but not of the gallows’ kind. And while Blaine is an entertaining fellow, that is not his sole purpose here. He—like most historians—is a lover of order. Murder succeeds in disorder.

And he is a lover of transparency and revelation. Murder festers in secrecy.

In short, Blaine has taken up arms in this effort for the restoration of a broken order. Daisy Zick is important—as important today as she ever was—and her unsolved murder calls out for solution, resolution and a reordering of history. This telling of her story is an important work, and I commend Blaine and his writing to your attention.

In Micah 6:8 of the English Standard Bible, we are called to our work: “He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?”

DAVID B. SCHOCK, PHD

David B. Schock, PhD, is a writer and filmmaker. His films about unsolved homicides include Who Killed Janet Chandler?, Finding Diane, Jack in the Box, Into the Dark, The Heritage Hill Bride and Murder on the Third Floor (the last two primary documentaries). In addition, he maintains a website, www.delayedjustice.com, that chronicles hundreds of Michigan murders. His most recent book is Judicial Deceit: Tyranny and Unnecessary Secrecy at the Michigan Supreme Court (with coauthor Chief Justice Elizabeth A. Weaver [retired]). In addition, he is an active musician.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

One must never set up a murder. They must happen unexpectedly, as in life.

Alfred Hitchcock

When you try to reconstruct a crime that is half a century old and unsolved, it can be challenging to say the least. One of the challenges I faced was whether I should use the real names of the people involved or substitute them with p

seudonyms. I opted to use the real names of individuals. My reasons for this are twofold.

First, I obtained the case file via a Freedom of Information Act request and countless interviews, as can anyone with the money and time. While people’s accounts were never validated under oath, their names and what they said are a matter of public record. The mentioning of a name in this book implies nothing more than that the person was, in some way, involved with the investigation or talked to by the authorities during it.

Second, this remains an open murder case. The use of real names may yet trigger memories and generate tips or leads that can lead police to close the case.

I am an author, not a detective. I approached the massive case file differently than a police officer would have. There are things I dug into, such as Daisy’s past, which an investigator in the case might not have. I don’t have any delusions about being the one to solve the case. My role here is to present the story as best I can, and I have tried to keep the focus solely on the details and facts that seemed pertinent to me in telling this story.

Solving this case, well, that is up to you. It won’t be solved by me as the author but by someone coming forward with new information and by good investigators who act on that information.

Finally, there are some accounts of people who were there that are impossible to reconcile with the documented case file. In some instances, memories are off with people; in others, the detail in the case file simply isn’t there. I have done my best to present the most accurate account of what happened starting on January 14, 1963. I apologize in advance if any minor mistakes were made.

I would like to thank the following people for their help. My apologies to any I may have missed:

Jim King—Daisy’s son. Jim provided me with a great deal of information on his mother and stepfather.

Dick Stevens—Dick is an icon in the legal circle of Calhoun County. His memories of events and people are remarkable.

Murder in Battle Creek

Murder in Battle Creek